Pablo Méndez-Lázaro is raising two children, navigating a global pandemic and developing an early warning system for Saharan dust and air quality in Puerto Rico. But when NASA asked him to help investigate how environmental factors may affect the spread of the novel COVID-19 virus, he was ready to answer the call.

“I was born in Puerto Rico and am proud to be raising a family here,” said Méndez-Lázaro, a professor at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus in San Juan. “A couple of weeks after Hurricane Maria, my one-and-a-half-year-old kid was admitted into the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) because of respiratory problems. It’s my mission to help protect fellow Puertorriqueños and it’s why I’m working to track factors for our air quality and health.”

Méndez-Lázaro noticed that his team’s use of NASA Earth observations for air quality could possibly help another goal: to better understand the risk factors of a global pandemic. He submitted a proposal to NASA to expand his research under the Earth Applied Sciences Health and Air Quality program area, and was among eight researchers recently awarded a rapid-turnaround project grant from NASA. These grants support investigators as they explore how COVID-19 lockdown measures are impacting the environment and how the environment can affect how the virus is spread.

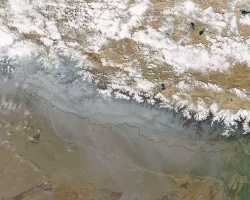

Now, Méndez-Lázaro’s team is examining if seasonal African dust, which travels to the Caribbean by riding air currents across the Atlantic Ocean, has significant impacts on health and mortality associated with the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Méndez-Lázaro and his team are working with epidemiologists, among many specialists, to better understand how African dust impacts public health.

Méndez-Lázaro is working closely with the Puerto Rico Department of Health, the National Weather Service’s San Juan Office, as well as physicians and patients, to gather information on people who have contracted respiratory diseases after exposure to African dust.

“We believe that there could be an exacerbation of COVID-19 patients in the Caribbean during African dust events,” Méndez-Lázaro said. “We see this as a Rubik’s Cube. Each tiny, colored cube is a different part of the puzzle.”

Méndez-Lázaro has worked at the University of Puerto Rico for 11 years, mostly focusing on climate change and impacts on public health. Before that, he received his doctorate in environmental science from the University of Salamanca in 2010, and his Bachelor of Arts in Geography from the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, in 2004. Méndez-Lázaro was born in Trujillo Alto and went to school in Santurce, Puerto Rico, where he always had a fascination with science and cared deeply about the natural world.

“I’m the youngest of four brothers, and our parents kept us in contact with Mother Nature. Most of our holidays were around outdoor activities, like sailing, surfing or camping,” Méndez-Lázaro said. “Since then, I’ve been in love with nature. Because of the unique experiences I had during my childhood, I felt the obligation to do more to protect the environment.”

Méndez-Lázaro is an active member of the Puerto Rico Climate Change Council and in 2018, was a co-author of the US Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4) for the Caribbean Region (Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands). In 2019, he was nominated by the governor of Puerto Rico and confirmed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate of Puerto Rico as a Scientific Advisor on Climate Change Adaptation at the Governor’s Office until 2024.

“Climate variability and extreme weather events associated with human-induced climate change can be considered the number one hazard threatening quality of life, public health and socio-ecological systems. Island nations are particularly vulnerable,” Méndez-Lázaro continued. That’s why he’s dedicated his career to using “new geospatial and communications approaches to facilitate efforts from public health practitioners and emergency response planners.”

In summer 2017, he was preparing an idea to track the movement of dust from the Sahara Desert across the ocean to see its effects on local air quality. Then, one of the most powerful storms to hit Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria, made landfall in his home commonwealth.

Méndez-Lázaro immediately got involved with first responders’ efforts. “Working on a medical science campus, with physicians and medicine, we were able to form a public health brigade five to six days after the hurricane, to visit communities unable to get access to medical services and supplies.”

In the wake of the hurricane’s devastation, portable electric generators installed by citizens and businesses to replace the power grid began affecting air quality in a new way that public health officials had not yet accounted for.

“My son Diego has asthma. He was in the PICU for one month after the hurricane, through the blackouts – he couldn’t breathe,” Méndez-Lázaro said. Diego recovered, but much of the monitoring capabilities in Puerto Rico collapsed or were destroyed, leaving the public without information to protect themselves. Méndez-Lázaro realized if he was able to validate satellite images using on-the-ground air quality monitors as a proxy, this tool could provide insight for authorities in their health decision-making.

Two weeks later, with electricity and phone lines still largely down, his team drafted a proposal to NASA Earth Applied Sciences’s Health and Air Quality program area. “It was a nightmare, it was so difficult to communicate or even type,” Méndez-Lázaro said. But now with NASA support, Méndez-Lázaro and his team have developed an air quality warning system that provides three days of advance notice about potentially harmful dust that travels to the island from the Sahara Desert.

Since then, the team’s work has been interrupted by political crises, earthquakes and a global pandemic. Despite these challenges, Méndez-Lázaro sees the opportunity to make things better for the future.

“Sometimes, it’s overwhelming when you try to get your head above water and these things push you back down,” he said. “But I’ve also seen them as opportunities to get stronger for Puerto Rico. A lot of learning experiences where, if we are smart enough to make it through, we can be better prepared for the future.”

When he’s not using satellite data to protect public health, Méndez-Lázaro loves to do anything outdoors – especially sailing, paddle boarding and biking with his family. He hopes his use of NASA Earth observations for public benefit will continue to make Puerto Rico a healthier place for his children and community for decades to come.

“It’s not only my personal or family conditions impacted by these kinds of events, but also the people near you or part of your team,” Méndez-Lázaro added. It’s important to have a group of support to hold each other in support, and we are not alone in the world.” He says that his mentors, Frank Muller-Karger of the University of South Florida, José Martinez-Fernandez of the University of Salamanca, and Juan Barragán of the University of Cádiz, have instilled the values of teamwork and community into every layer of his research.

As a result, Méndez-Lázaro’s life and career lead by example – his work could help empower patients, health providers and communities to protect public health for generations to come.

Read more about Pablo Méndez-Lázaro's work at the NASA.gov story, NASA Helps Puerto Rico Prepare for Saharan Dust Impacts.