About 60% of Washington state residents live in the Seattle metropolitan area, a bustling seaport and one the fastest growing cities in the U.S. The rest of the state is awash in dense forests and the rugged Cascade Mountains that divide the “Wet Side” and “Dry Side” of the state.

As in many other Western states, wildfires regularly encroach on Washington’s natural beauty, and in 2015, Washington had its one of its worst wildfire seasons. One year later, more wildfires were threatening the area. Responders used a NASA post-fire decision-support system that taps into satellite data to quickly identify at-risk areas and plan recovery responses in the wake of a wildfire.

In 2015’s wildfire season, particularly devastating was north-central Washington’s Okanogan Complex Fire that scorched more than 300,000 acres of land and killed three firefighters. Just a year later, more wildfires were blazing across the landscape near metropolitan Spokane. Katherine Rowden was returning from the movies with her daughter when she saw the ominous signs on the horizon.

“You could see smoke plumes on both sides of town, which is not a common occurrence,” she said. As a service hydrologist for the National Weather Service Office in Spokane, Rowden has analyzed the aftermath of many fires. “Usually I hear about wildfires while I’m at the office; but in this case, it was right in my backyard.”

As firefighters worked to contain the Spokane fire, Rowden’s job was to prepare for the aftermath – the potential for flash flooding. After a fire, the combination of charred soil and lost vegetation often means that any subsequent rainfall runs right off rather than being absorbed in the ground.

“Because of the flash flood risk that remains after a fire, I work closely with many professionals from different backgrounds to assess risk, inform the public, and help warn of possible flash floods,” she said. “To do that, I need to have an estimate of how the fire affected the landscape.”

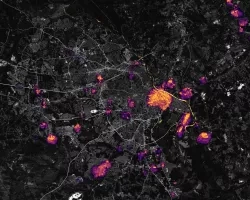

Rowden turned to the Rehabilitation Capacity Convergence for Ecosystem Recovery (RECOVER) system for more information about the fire. RECOVER is an online mapping system that automatically integrates a multitude of remote-sensing data and imagery from satellites to produce near real-time updates of a wildfire’s effect on the land.

RECOVER was developed by NASA, Idaho State University (ISU), and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management. “RECOVER is a post-fire decision-support system that rapidly provides actionable information in the wake of a wildfire,” said Keith Weber, GIS director of ISU and principal investigator for RECOVER. “RECOVER provides post-fire data describing the event, such as fire severity, and helps identify areas in need of reseeding or other post-fire treatments.”

For Rowden, having a fire intensity product is crucial to her post-fire work. “[It] is a remote-sensing estimate of the fire’s effect on the vegetation – a pre- and post-fire comparison. Having that information as quickly as possible allows us to get a feel for where the really problematic spots could be. That’s because the more severe the fire’s effects are on the ground, the worse the post-fire floods and debris flows can be,” she explained.

“Without [a single imaging resource], I would be spending time trying to wrangle data from multiple agencies instead of working on the post-fire reports and helping the team members.”

–Andrew Phay, Whatcom Conservation District

Rowden and a team of scientists, which included Andrew Phay, a wildfire GIS specialist from the Whatcom Conservation District in Lynden, Washington, used RECOVER to create a soil burn severity map.

“The fire can affect the chemistry of the soil,” Rowden explained. “Severely burned soil can actually repel water, so it’s more like a raindrop hitting pavement than hitting a forest floor. And this makes a big difference as to how much water is coming off during a subsequent storm.”

With the map, Rowden looked at what was downhill. “In this case, fortunately, most of the homes were out of harm’s way of catastrophic flooding or debris flow risk,” she noted. “In other cases, there certainly are risks, so RECOVER can be key in figuring that out and being confident in that final risk assessment.”

With the assessment completed, Rowden and her team then reassured several partners – including the Washington State Department of Ecology (WDOE) and the Spokane County Public Works – that the risks to their interests were minimal. Specifically, WDOE had concerns about the post-fire impacts on a nearby creek. “We told them that there was going to be some erosion and there would probably be some water quality impacts; but there weren’t any immediate, catastrophic risks expected”

Phay emphasized that having this guidance available from a single resource like RECOVER was key to the team’s quick assessment of the Spokane fire. “Without it, I would be spending time trying to wrangle data from multiple agencies instead of working on the post-fire reports and helping the team members.”

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.