Over several days in the summer of 2019, a cluster of earthquakes shook Southern California. While no major casualties were reported, these earthquakes still left their mark on the land. NASA scientists can measure how such events disrupt and move the land surface.

The biggest earthquakes – a magnitude 6.4, followed by a stronger magnitude 7.1 – occurred on July 4 and 5 near the town of Ridgecrest. Thousands more aftershocks rumbled, most of them too small to be felt by humans.

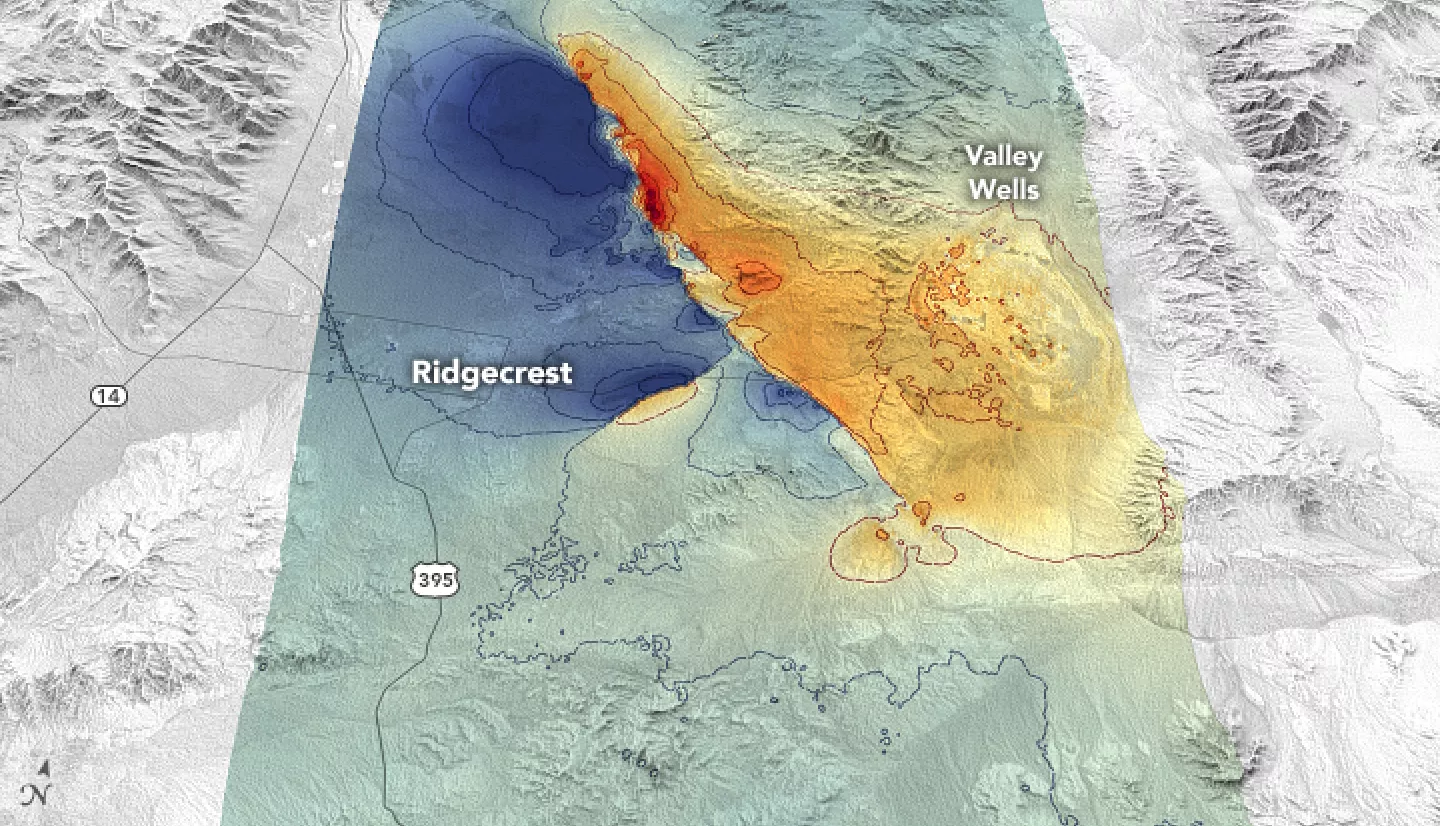

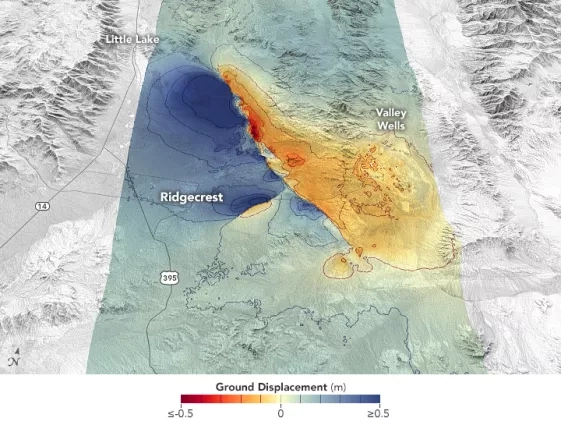

The Advanced Rapid Imaging and Analysis (ARIA) team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the California Institute of Technology’s Seismological Laboratory produced maps of the ground displacement. Some land shifted several feet vertically, horizontally, or both.

These maps showed how the first earthquake probably triggered the larger one on a nearly perpendicular fault. Land on the west side of the fault moved by as much as 0.8 meters (2.7 feet). Areas to the east moved by as much as 0.6 meters (2 feet).

Japan’s ALOS-2 satellite provided the ARIA researchers with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data for their analysis. By bouncing radio signals off the ground, SAR instruments can measure the distance between Earth’s surface and the satellite. SAR images taken of the same spot on different days can reveal how much the land surface has shifted.

NASA provides these maps to the California Geological Survey, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the U.S. Geological Survey. These agencies track which areas have higher likelihood of future earthquakes.

“The SAR data were very useful for field mapping teams to help guide them where faults are located,” said Chris Milliner, a geophysicist at JPL. He said the data uncovered many more faults than anticipated, “which might have been missed in the field without this remote guidance.”

More information available at the NASA Earth Observatory story Measuring Movement from the Ridgecrest Quake.