Bordered by five states, the Gulf of Mexico is the world’s ninth-largest body of water. More than 14 million people live along the Gulf’s 1,680 miles (2,704 kilometers) of United States coastline. Along with its inviting beaches and warm climate, the Gulf is also host to thousands of petroleum drilling platforms and is a major source of America's oil production. “With more than 3,800 platforms in the Gulf of Mexico, I thought that one day an oil spill might happen,” said Sonia Gallegos, an oceanographer with the Naval Research Laboratory.

Gallegos also thought that Earth-observing satellites could help improve and automate the detection of oil on the surface of the Gulf. With that focus, she led a project team composed of scientists from the laboratory, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Center for Satellite Applications and Research (NOAA STAR).

Gallegos’s team collected data from U.S., European and Japanese satellites that look at the water, land and clouds to understand the oil dispersion and submersion in the water, as well as what happened to the oil slicks closer to land.

Then, only six months into the project, the worst oil spill in the Gulf’s history occurred – the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010. Gallegos's team immediately shared the data and resources it had acquired with other agencies and universities involved in the disaster response.

The team also used space-based and airborne lidar (which works like radar, but uses laser light) to investigate the thickness of the oil spill below the water’s surface and evaluate the effectiveness of dispersants, which are used to break up the oil. When the project wrapped up, the team transitioned its findings – which included new algorithms for providing rapid and enhanced spaceborne monitoring of oil spills – to NOAA STAR to guide NOAA’s response to future spills.

Four years later, another waterborne menace fouled Gulf Coast beaches. It wasn’t crude oil this time, but huge masses of a brown, vine-like seaweed called Sargassum. In open water, Sargassum serves as a habitat for marine life, but when large amounts of it periodically wash up on shorelines, they create pungent piles filled with decaying sea organisms, marine debris and medical waste.

It’s not just uncomfortable to walk through Sargassum on your way to the water, explained Claire Reiswerg, co-owner of Sand ’N Sea Properties of Galveston, Texas. “We warn [our guests and clients]: if it's thick, watch out for debris and watch out for glass, because it is a health and safety issue.”

“What makes this unique is the use of satellite imagery provided by NASA, and without it, this system would not be possible.”

–Tom Linton, TAMU-Galveston

The massive Sargassum landing of 2014 was so dense, it collected into 10-foot (3-kilometer) mounds in Galveston – the worst such incident in 50 years. This time around, communities along the Texas Gulf Coast were more prepared for the invasion, thanks to a 2012 NASA-Texas A&M University project.

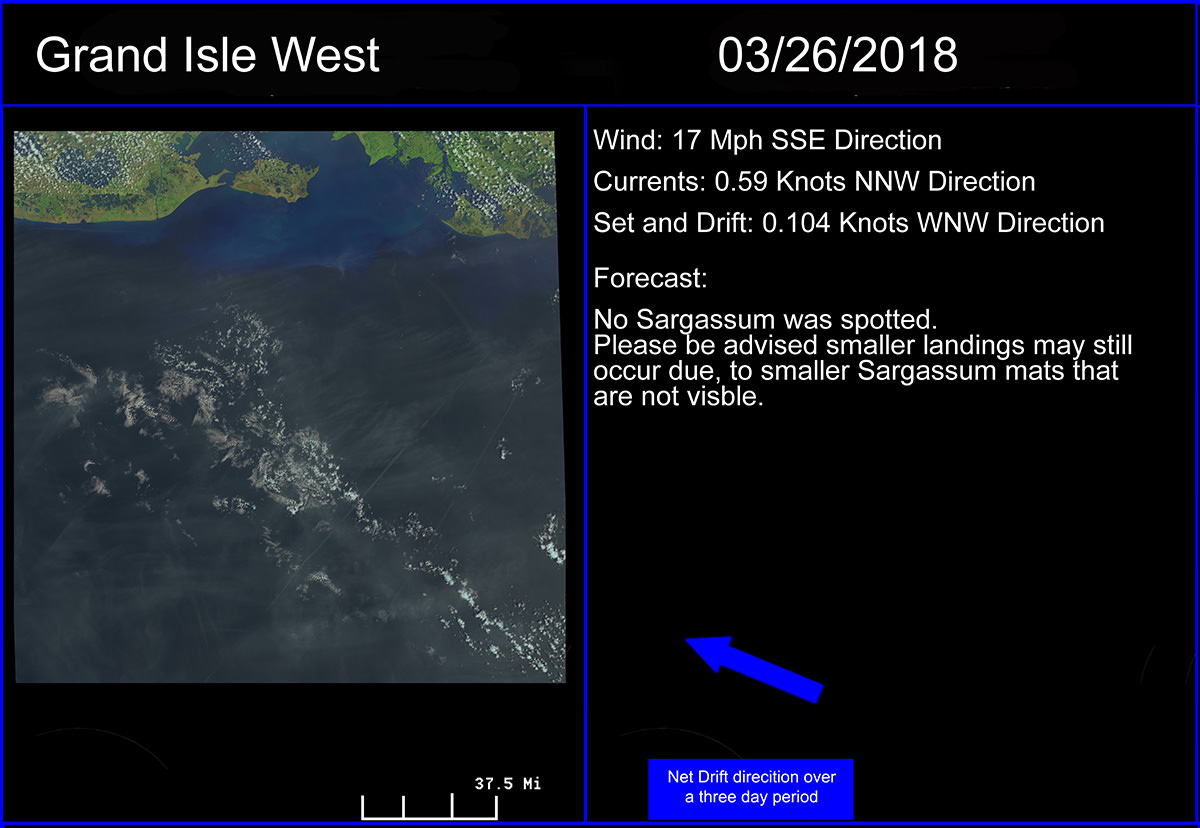

The project team incorporated land-observing satellite data, an ocean circulation model and NOAA wind data to create a seaweed forecasting tool called the Sargassum Early Advisory System. As early as 2013, the system's team was issuing Sargassum-landing advisories to Texas coastal managers, allowing them to more efficiently schedule personnel and to target when they’d need to rent equipment for Sargassum removal.

Since then, this early advisory system has become a game changer for coastal managers. Before, “they never knew it was coming in,” Reiswerg said. “They never knew how much equipment they needed. So, inevitably, there wasn't enough equipment, or there weren't enough personnel on duty that day … It was a very reactive system.”

Reuben Trevino, a coastal resources manager with the City of South Padre Island, Texas, agreed and emphasized, “It has really improved our ability to prepare for what is headed in our direction.”

In another milestone, the scientists at Texas A&M unveiled a mobile version of the Sargassum Early Warning System. Tom Linton, a marine scientist at TAMU-Galveston who helped develop the app said, “As far as we know, this is the only app of its kind in the world. What makes [the application] unique is the use of satellite imagery provided by NASA, and without it, this system would not be possible,” Linton said.

The mobile app can forecast the direction of the seaweed’s travel, and even predict the hour it should hit a certain part of the coast. “A wide variety of stakeholders, such as beach managers, fishermen, tourists and the public, will benefit from this new app,” he added.

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.