Earth observations are aiding the mission to end river blindness

When a former president of the United States asked for assistance in eliminating a debilitating disease from the Americas, it was a challenge we decided to take on.

Scourge of Millions

"My daughters must cook my meals, clean the house, and help me dress."

That is how river blindness changed Pitasia Gonzales of rural Mexico. She acquired the disease many years ago and it not only took her sight, it also stole her independence.

River blindness, or onchocerciasis, is an affliction caused by a parasitic worm that’s transmitted person-to-person by the bites of Simulium sp. black flies. It gets its more common name due to the fly’s breeding grounds along fast-flowing rivers and streams, as well as the disease’s tendency to cause vision loss for its sufferers, among other debilitating symptoms.

Since its inception, The Carter Center’s Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the  Americas has had one goal—ending the disease in North and South America. The program works with six afflicted nations in the Americas administering safe and effective ivermectin tablets (Mectizan®, donated by Merck) in afflicted communities. Through determined work by the ministries of health of these countries, the transmission of river blindness has ended in Gonzales’ native Mexico, as well as in Colombia, Ecuador, and Guatemala.

Americas has had one goal—ending the disease in North and South America. The program works with six afflicted nations in the Americas administering safe and effective ivermectin tablets (Mectizan®, donated by Merck) in afflicted communities. Through determined work by the ministries of health of these countries, the transmission of river blindness has ended in Gonzales’ native Mexico, as well as in Colombia, Ecuador, and Guatemala.

As of 2015, the threat from river blindness in the Americas remained only in the dense rainforest area along the Venezuela and Brazil border, where the native Yanomami people live.

The Letter

President Jimmy Carter made his mission for 2015 clear: “By the end of this year, all river blindness-affected Yanomami communities need to be identified so we can begin to provide villages with medicine and health education.”

Then came the letter. Addressed to NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, it was a request from President Carter to help Venezuela locate any remaining unidentified villages in the deep Amazon rainforest. President Carter had personally visited the Yanomami before and knew how difficult it was to find these villages. And NASA, with its ‘eyes in the sky’ imagery, was ready to help provide the new information to locate villages that were not yet registered by the health system.

Still, it wouldn’t be easy, and making the task more difficult was the fact that the Yanomami migrate frequently due to shifting land suitability and food supplies. They also tend to remain close to rivers—prime habitat for the black fly.

“Thanks to NASA’s work, we are able to feel more confident that the country is truly tracking down any possible last vestiges of river blindness in this exciting elimination effort.” Frank Richards, The Carter Center

Scanning the Amazon

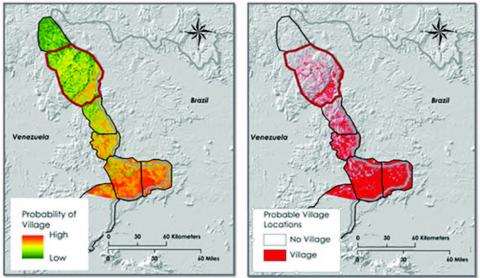

NASA’s Applied Science DEVELOP program, with its flexibility and expertise, took on this project. Using Earth observations from Landsat and ASTER, along with data provided by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, three DEVELOP teams collaborated on a project to help The Carter Center with its mission.

The result was an interactive map with latitude/longitude coordinates, associated imagery, and approximate populations (based on hut roof areas) for all potential Yanomami villages that were identified. For areas where there were questionable settlements, the team created a suitability model that identified areas where the Yanomami would likely inhabit.

The End in Sight

In total, the project team found evidence of more than 160 potential villages, generally identifiable by their shabono, which are open, oval huts constructed in rainforest clearings. Many of these were anticipated to overlap with the known 460 endemic Yanomami communities; however, the assumption was that some would be new to the system. The team presented its information and methods, which included an interactive map in Google Earth, to The Carter Center in August 2015.

The following month, The Center shared this new information with the Venezuelan river blindness health workers, who later determined that 16 of the villages discovered were previously unknown to them. Subsequent fly-overs of four of those villages in 2015 confirmed that they were inhabited. One was visited on foot, and determined to be non-endemic for river-blindness. Venezuela intends to visit all the newly discovered villages in 2016.

“We are thrilled with the results of this project. And even for the villages that are ultimately found not to be endemic for river blindness, the country will now be able to offer other needed health services where they were previously unavailable,” said Frank Richards, director of The Carter Center River Blindness Elimination Program.

As this mission continues, The Carter Center is driven to give the Yanomami what it gave to Pitasia Gonzales—hope for the future. After her grandchildren received preventative treatment from The Center, Gonzales was optimistic. "Their generation has the opportunity to preserve its vision."

Michael Ruiz leads our DEVELOP program.