When you think of penguins, Rhode Island is likely not the first place that comes to mind. But more than 7,000 miles (11,265 kilometers) away from The Ocean State, penguins are helping guide the operations of the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) – a nonprofit trade association located in South Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Working with scientists, the association uses NASA satellite data that detects the "signature" of penguin excrement to help operators plan their visits to Antarctica without adverse impact on the birds.

Rhode Island is the global hub of IAATO, which boasts a membership of 105 companies and organizations from around the world. “Virtually all Antarctic tour operators are members of IAATO, which means they are all showing commitment to environmentally safe, private-sector travel,” said Amanda Lynnes, IAATO’s Director of Environment and Science Coordination.

A large part of that commitment is making sure IAATO’s members reduce or eliminate their impact on Antarctic’s protected areas and wildlife.

"Virtually all Antarctic tour operators are members of IAATO, which mean they are all showing commitment to environmentally safe, private-sector travel. MAPPPD helps the Antarctic community, including IAATO, manage human activity.”

–Amanda Lynnes, IAATO

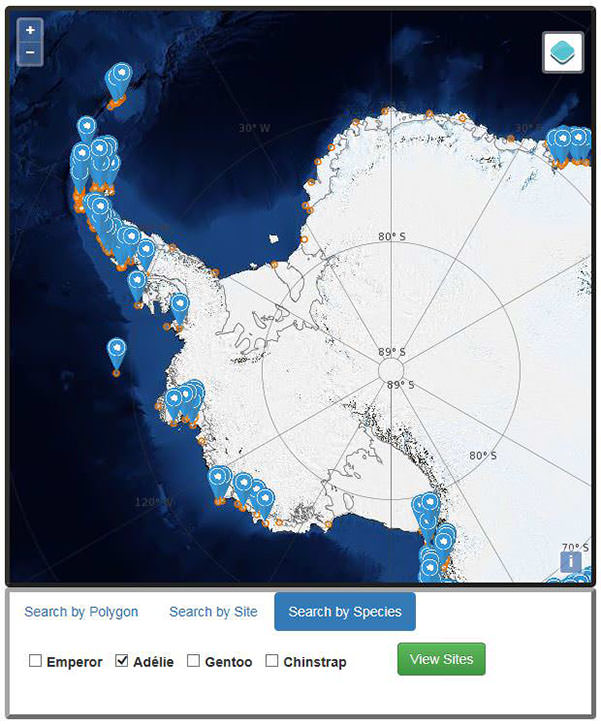

To do this, IAATO uses an online database called MAPPPD, or Mapping Application for Penguin Populations and Projected Dynamics. MAPPPD is the result of a NASA Earth Applied Sciences project that uses satellite data to provide an assessment of the locations and abundance of four penguin species across the frozen continent. It was created by the conservation foundation Oceanites, Inc. in partnership with Heather Lynch of the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and Mathew Schwaller of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

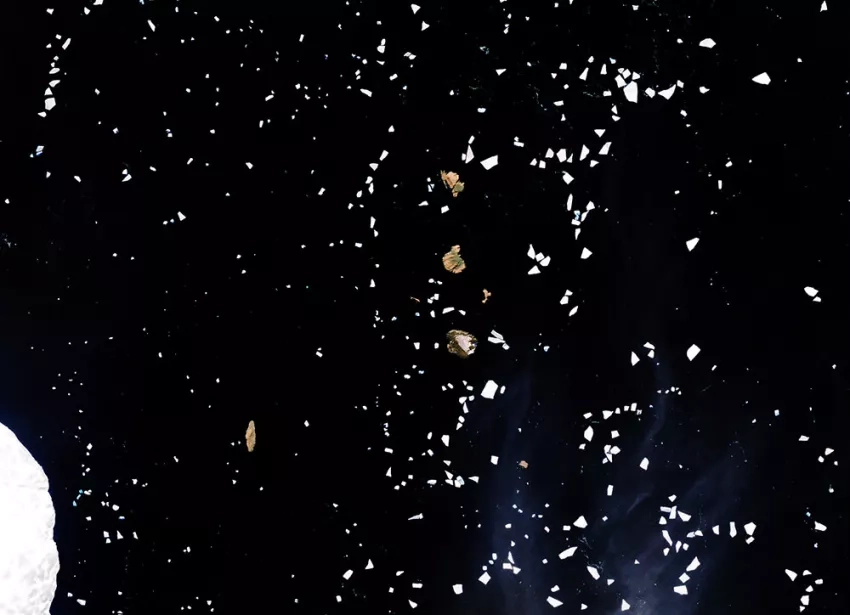

How does a satellite monitor the whereabouts of small, aquatic birds? It detects the “signature” of their excrement.

“Satellite-based penguin surveys are detecting the guano left behind by penguins nesting at the colony,” Lynch explained. “Male and female penguins take turns incubating the nest … and the guano left behind builds up in exactly the same areas occupied by the nests themselves. We can use the area of the colony – as defined by the guano stain – to work back to the number of pairs that must have been inside the colony.”

With these “poo views,” MAPPPD automatically classifies penguin areas, generates abundance estimates, and then pushes that information to the database to update models in real-time. And it includes more than just satellite data. “MAPPPD also continues to serve as a hub for ground-based surveys and for data coming from citizen science efforts,” said Lynch.

That aspect of MAPPPD is especially important to IAATO. “Many Antarctic visitors are offered the opportunity to participate in citizen science, which is the practice of involving members of the public in scientific projects,” said Lynnes. “It is a powerful tool for building scientific knowledge, public engagement, and education.”

But IAATO isn’t just about responsible tourism. During the 2018-2019 season, IAATO operators transported more than 130 support, conservation and scientific staff – and their equipment and supplies – between stations, field sites and gateway ports in Antarctica. And they used MAPPPD for its guidance. “MAPPPD helps the Antarctic community, including IAATO, manage human activity,” Lynnes said. “This must always be a collaborative effort.”

For the penguins half-a-world away from Rhode Island, IAATO’s advocacy is giving them a warm and fuzzy feeling in their icy world.

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.