Blizzards, narwhals and sneaky polar bears are all part of a day’s work for Kristin Laidre, a marine biologist funded by NASA’s Applied Sciences Ecological Forecasting Program to study glaciers in southeast Greenland and the polar bears that use them as a habitat.

Laidre spends a lot of time in the Arctic, especially in Greenland where she is using GPS to track polar bears, among many other research efforts.

We sat down with Laidre to ask her what it’s like working in one of the most isolated places on Earth, what big question she’s trying to answer, and why the title of her autobiography would be “Things I Didn’t Tell my Mother: All the Ways I Almost Died.”

1. What’s it like working in the Arctic?

It’s so unbelievably beautiful. There are these huge jagged mountains covered in snow and glaciers coming down from the ice caps. There are polar bears, seals and nobody for a thousand miles. It’s just kind of unreal. But aside from the Arctic’s beauty, there are a lot of challenges you face there that you can’t really control or predict.

Often the challenges involve weather, which is a huge factor for doing anything in the Arctic. On any Arctic project I’d say about 50% of the days you can’t work because the weather is so bad, so on the days you can work you have to do things as efficiently as possible.

2. What is the biggest question you’re trying to answer?

Climate change is impacting all of the animals that I study, so it’s sort of like a theme that is always there across my projects, but we also study populations for other reasons, such as ensuring sustainable use of natural resources by indigenous communities. The big question we’re trying to answer is what does the future look like for all of these uniquely adapted Arctic mammals?

In 50-to-100 years, how many of these animals will be left and how will that impact the ecosystem? All the work we do as scientists documenting these changes is so important.

3. What advice to you have for young scientists coming into the field?

Stay positive, be creative, and work hard. There’s many ways a young scientist can contribute, but increasingly those of us who work on the front lines of climate change have to work hard to not let the difficult things we are documenting affect us in a negative way.

It’s hard to see a lot of the things we observe and what we document. Everyday you’re living the reality that things are really going downhill fast due to climate change, so staying positive will be so important for young scientists going into the field.

4. What would your autobiography be titled?

Things I Didn’t Tell my Mother: All the Ways I Almost Died. We care so much about safety, but there are things you just can’t control in the Arctic. You deal with so many unexpected things, from really dangerous weather to polar bears sneaking up on you.

5. Wait… polar bears will sneak up on you?

It usually happens when you’re working with another polar bear that is sedated. I’ve had encounters where a different polar bear will see me from far away and must think “that looks interesting.” I’ve had a polar bear get on its belly and put its nose through the snow so you couldn’t see the black part and crawl army style to sneak up on me; so, you have to be very vigilant.

6. What led you to write a graphic novel about the narwhal and its tusk?

There’s a lot of misinformation in the media about the purpose of the narwhal tusk—for a long time people thought it was a sea monster that could use its tusk to destroy ships. Every time I do any outreach or school talk on narwhals I get asked about their tusks, and I grew frustrated about the incorrect information out there.

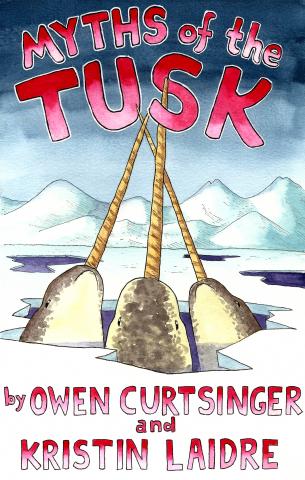

I wanted something creative and funny that was also factually correct which I could share with people and get them to learn about the information in a different, human way. I worked with an artist I know, Owen Curtsinger, to bring the story of the narwhal to life

You can view Myths of the Tusk at Owen Curtsinger's website.

Laidre plans to return to the field next year in 2020 in east Greenland, where she will be continuing her research on polar bears and their changing habitat.