Asthma is the most prevalent chronic respiratory disease worldwide; affecting 358 million people in 2015—including 14 percent of the world’s children.

Scientists have long known that breathing in air sullied by car emissions and other pollutants could trigger asthma attacks. However, a new study supported by NASA’s Health and Air Quality Applied Science Team (HAQAST) is the first to quantify air pollution’s impact on asthma cases around the globe.

“Millions of people worldwide have to go to emergency rooms for asthma attacks every year because they are breathing dirty air,” said Susan C. Anenberg, lead author of the study and an Associate Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. Anenberg, who is also a Co-Investigator of HAQAST, added, “Our findings suggest that policies aimed at cleaning up the air can reduce the global burden of asthma and improve respiratory health around the world.”

Previously, studies estimating the burden of disease from ambient air pollution have focused on quantifying the impacts of air pollution on heart disease, chronic respiratory disease, lung cancer, and lower respiratory infections – but the impacts on asthma have not been included.

“We know that air pollution is the leading environmental health risk factor globally,” Anenberg said. “Our results show that the range of global public health impacts from breathing dirty air are even more far reaching—and include millions of asthma attacks every year.”

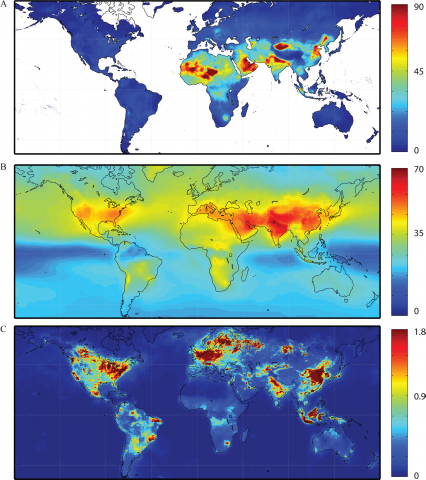

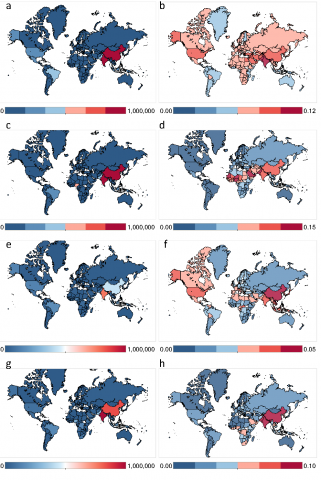

What is the impact? Nine to 33 million visits to the emergency room for asthma worldwide may be triggered by breathing in air polluted by ozone or fine particulate matter—pollutants that can enter the lung’s deep airways, according to the studypublished today, Wednesday, October 24. The new findings, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, suggest car emissions and other types of pollution may be a significant source of serious asthma attacks.

For this study, Anenberg and her team first looked at surveys of emergency room visits for asthma in 54 countries and Hong Kong, and then combined that information with epidemiological exposure-response relationships and global pollution levels. To estimate the global levels of pollution for this study, the researchers turned to atmospheric models, ground monitors and satellites equipped with remote-sensing devices—including NASA Aura’s Ozone Monitoring Instrument.

“The value of using satellites is that we were able to obtain a consistent measure of air pollution concentrations throughout the world,” said HAQAST’s Daven Henze, Principal Investigator on the project and an associate professor for the University of Colorado Boulder. “This information allowed us to link the asthma burden to air pollution even in parts of the world where ambient air quality measurements have not been available.”

The new research suggests that about half of the asthma emergency room visits attributed to dirty air were estimated to occur in South and East Asian countries, notably India and China. Countries like India and China may be harder hit by the asthma burden because they have large populations and tend to have fewer restrictions on factories belching smoke and other sources of pollution, which can then trigger breathing difficulties, the authors said. Although the air in the United States is relatively clean compared to South and East Asian countries, ozone and particulate matter were estimated to contribute 8 to 21 percent and 3 to 11 percent of asthma ER visits in the United States, respectively.

In terms of applying this study’s findings, Anenberg suggests that policymakers aggressively target known sources of pollution such as ozone, fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide. She says policies that result in cleaner air might reduce not just the asthma burden but other health problems as well.

One way to reduce pollutants quickly would be to target emissions from cars, especially in big cities. Such policies would not only help people with asthma and other respiratory diseases, but it would help everyone breathe a little easier, she said.

In addition to Anenberg and Henze, the international, multi-institutional research team also included scientists from the Stockholm Environment Institute, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, and others.

Read the full press release from George Washington University.