The Sendai Series || 1

This is the first in a series of articles profiling NASA’s role in contributing to the Sendai Framework, a United Nations initiative to help communities worldwide manage, mitigate and plan responses to a wide array of disasters. The Sendai Framework was adopted by U.N. member states on March 18, 2015 during a conference on disaster risk reduction in Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan.

They may come in the dead of night or during the light of day. They know no boundaries, and respect neither national authority nor moral imperatives. They create only tragedy, leaving behind destruction, ruin and, often, death.

Yet despite everything that disasters ravage and wreck, all may not be lost. Anticipating and preparing for the worst can diminish some of the potential devastation. That’s where NASA comes in: leveraging the expertise of specialists and a constellation of orbiting satellite instrumentation to analyze and anticipate areas most in need of help, ideally before, but also during an event and thereafter, as officials work to protect the most vulnerable populations and communities.

“We’re taking Earth observations made by satellites to make a difference on the ground,” said Shanna McClain, NASA’s Disasters Program lead for risk and resilience. “It’s not just pulling data and seeing if it’s beneficial. Our goal is to look at the risks beforehand: to help communities build better, plan more proactively.”

Such an approach is on vivid display in a number of Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, where nearly 750,000 Rohinhya have fled since August 2017. Many have sought shelter in encampments on the hilly countryside, where landslide risk may be the greatest. Increasing this danger is Bangladesh’s intense monsoon season. NASA data on land use, rainfall and elevation is helping camp managers to decide where best to place the camps — and identifying those areas that may be too unstable to even store supplies.

Evaluating Risk, Safeguarding Communities

In a commemoration that began in 1989, every October 13 the United Nations observes the International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction. The remembrance is intended to underscore how people and communities around the world are reducing exposure to disasters while also raising awareness of the importance of reining in the risks that they face.

The ability to model disasters’ worst effects and where they’re likely to occur has become an essential approach in decreasing exposure and increasing resilience. NASA research is leading the way. In 2019, the Disasters Program announced a series of multi-year grants to researchers, both in and outside NASA, to explore means of predicting effects from landslides, flooding, earthquakes and other potentially catastrophic events so that planners and other decisionmakers can devise the best approach to avoid loss of life and property and minimize the effects of economic disruption.

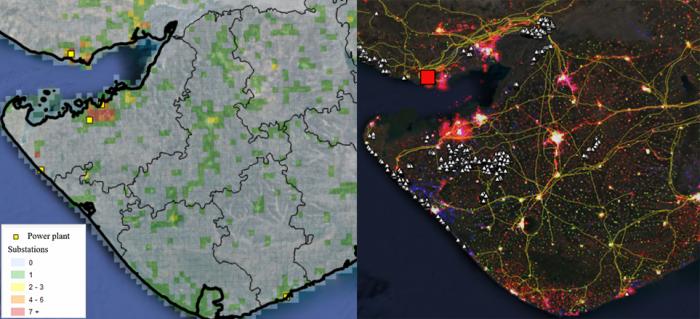

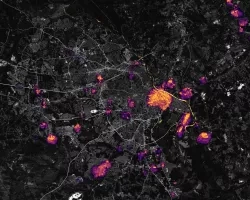

One of those grantees is Charles Huyck, executive vice president of the Long Beach, Calif. firm ImageCat, which specializes in risk-management technologies. Huyck leads a research group that intends to improve computerized models that marry satellite-based Earth observations to geographical information systems that depict disaster-related impacts of severe infrastructure disruption.

“These are problems we should be able to predict. It’s an international priority,” he said. “We’re working to identify the areas that are most vulnerable: especially the lifelines. Being able to model these things is essential to predict where the most severe effects are likely to occur.”

Huyck’s team is exploring how cities with interconnected “lifeline networks” of critical infrastructure can be severely damaged or destroyed in the aftermath of natural disasters. Following Hurricanes Maria in 2017 in Puerto Rico and Katrina in 2005 in Louisiana, and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and resultant tsunami in Japan, for example, damage to vital systems resulted in cascading effects that severely impeded recovery and disabled regional economies.

In many cases the location of key components is unmapped or unshared, particularly in developing countries. Without pinpointing the physical location of essential assets, it is not possible to identify where the regional risk from infrastructure disruption can lead to cascading damage that, in some cases, could significantly reverse economic progress.

Disasters’ Interlocking Fallout

But it’s not just a single threat presented by a single debilitating event. One disaster can trigger another, as happens when heavy rains trigger landslides and mudslides following wildfires or periods of long drought. In addition, there is the potential for what is becoming known as “Natech”: [a] Natural Hazard Triggering Technological Disasters.

Notes a U.N. report on the subject:

The impacts of natural hazard events on chemical installations, pipelines,

offshore platforms and other infrastructure that process, store or transport

dangerous substances can cause fires, explosions, and toxic or radioactive

releases. Although these Natech accidents are a recurring feature in many

natural disasters, they are often overlooked, despite the fact that they can

have major social, environmental and economic impacts.

“What’s starting to happen globally is a recognition that disasters can be huge setback for growing economies,” Huyck said. “We’re developing ways to estimate [potential] building losses in developing economies: Here’s what might happen, and here are the resources that can be mobilized to mitigate those losses.”

The economic effects, while often upstaged by dramatic images of severe devastation, can likewise be catastrophic. Huyck cites the 2011 landfall of Tropical Storm Nock-ten in Thailand, which caused a global shortage of hard disk drives that persisted throughout 2012. Citing figures released by the Thai government, news agency Reuters reported economic losses were estimated to be at least $8 billion.

“The whole purpose of this work is to identify opportunities to fill gaps and work toward risk reduction and resilience,” said Disasters Program Manager David Green. “At NASA we’re promoting scientifically defensible studies, projects and demonstrations of actual applications. We want to collaborate as widely as we can. The ultimate goal is to protect and, in protecting, create as much sustainability as possible.”